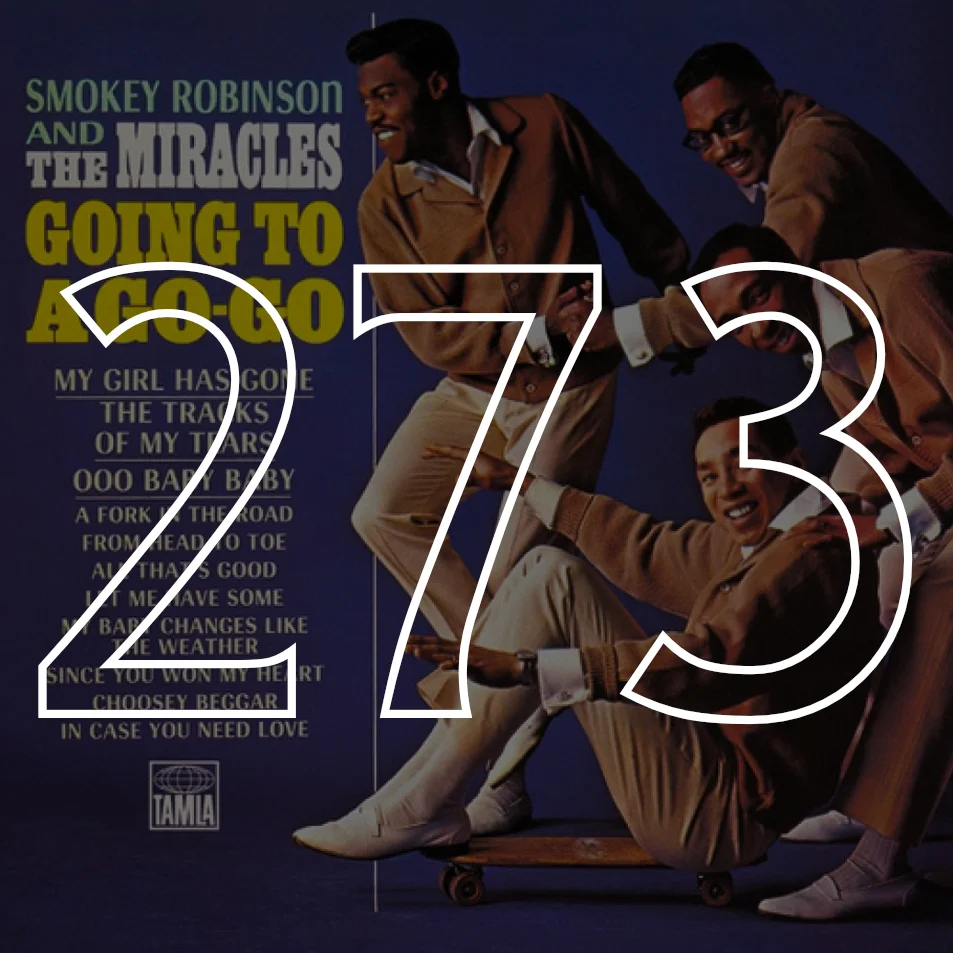

#273: Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, "Going to a Go-Go" (1965)

for Ben

Last night I was listening to Going to a Go-Go with my friend Ben, who has a story about a Canadian soldier who was lying in state, a soldier named Smokey. In this story, Ben's friend works as a tour guide in Canada's Parliament building, and in the course of giving this standard tour the friend informs the tourists, or rather misinforms them, that the Smokey-in-state is none other than Smokey Robinson. This is not my story, so I can't really be more specific than that, and in telling it in this way I've ruined the punchline, which would have been the point in the first place if I was going to construct this analogy between a pop album primarily focused on heartbreak and yet which—like so many great pop albums—takes it as an occasion for sounding a little sunny. And anyway, the story is Ben's and not mine. Can I write about a pop album using someone else's anecdote?

I want to be clear that this is a formal and compositional problem more than an ethical one. Or, if it's ethical, then unfortunately I intend to be callous about it. I don't think that rarefying personal experience is the best window into thinking about all the complexities of our relationships to objects. In this sense we relate to objects pretty much the same way we relate to pop music: what is "personal" about it is ultimately something fairly un-individual and generic; it's built into the songs themselves. For example, I was going to write about the guitar in "My Girl Has Gone," a delicately strummed introduction that soon vanishes beneath the exuberance of the orchestration that accompanies the song's ironic hook about heartbreak. But when I looked up the album on Wikipedia—is it OK to admit I did this? how does this differ from using Ben's story about someone else's story as a springboard for this piece?—some anonymous editor had already praised Marv Tarplin's "startling guitar riffs."

And yet—this is a misreading. The word in the Wikipedia is "starting" and not "startling." Either way it's fairly inadmissible, for, as we all know, citing Wikipedia is unacceptable in essays. Is this the kind of essay in which citing Wikipedia is unacceptable? Am I "citing" it in the uncitable, unacceptable way? All these questions I've accumulated since the beginning of this piece are questions about textuality, that variegated constellation of representational strategies we deploy (sometimes without even thinking about it) constantly to organize our perceptions of the world. Textuality is the "l" I added into the word "starting" on Wikipedia: it's the small mediation that gives the lie to the "immediacy" of whatever we experience as immediate, the minimal distance between us and the sheer empirical data that constitute "existence" that we sometimes notice and which sometimes startles us because it feels almost like a mistake that we realize: "there wasn't an 'l' in the word after all, it was just 'starting'" or "this story is Ben's story about someone else's story: can I tell it?"

It's no accident that this roundabout writing about pop music has landed on the theme of textuality. Most writing about pop music is writing about textuality. It's hard to argue otherwise: the sorts of tonal asymmetries that I mentioned above—upbeat songs about downbeat themes—are almost instantly recognizable, to the point where when I write them down it feels like I'm telling you something you already knew. Part of the reason I'm having so much trouble writing about Smokey Robinson is that you've heard Smokey Robinson before: either the artist himself, or the music for which "Smokey Robinson" is the name for a complex set of devices, an arsenal of techniques to achieve specific sonic effects. So what do I have that is not a value-superlative, to tell you about this album that you probably know, whether you know you know it or not?

Nothing, except maybe this anecdote about a dead Canadian soldier, and it's not even my story, it's Ben's story—or, it's Ben's friend's story he's kindly shared with me. So I have my friendship with Ben, the textuality of this friendship. But how can a friendship commend to you an album, let alone give an account of it? Fond as I am of giving accounts of things, I'm trying something else out. Let me close with my own anecdote:

Last night Ben and I listened to Going to a Go-Go all the way through together. Most of the way through the album we sat quietly and listened to a kind of music we both knew well already and were already fond of. Call it "Motown," call it "Smokey Robinson," it doesn't matter. The point is it was very familiar, though no less pleasurable for the feeling of immediate recognition, of non-strangeness. Then came the album's last song, "A Fork in the Road," which begins with Robinson and the Miracles blithely harmonizing on the word "beware" over a delicate, mid-tempo arrangement of strings and xylophone. The song's title derives from the lyric, "although I may be just a stranger / lovers, let me warn you: there's a danger / of a fork in love's road." And as Robinson sang this over the same almost dreamy instrumentation Ben looked at me and said "this is nice; the whole album is nice, but this ends really nicely." I agreed, which I guess you knew already, because if I hadn't I wouldn't have written it into this piece, used it as a mediation of how I think pop music is a strange cipher for textuality, whose lessons I feel like I need constantly to remind myself of so that I can do things like write. But let us not forget the other text sitting alongside Ben's text, the text of Robinson's lyric, the danger of a fork in love's road. Is this not also start(l)ing to hear or to think about, pop music as the reminder that everything has the capacity to appear to be the same as everything else, but that doesn't mean that the fork in the road goes away? In fact it maybe intensifies that fork. And that was when Ben said, "let me tell you about Smokey Robinson [NB: who is not dead] lying in state." And that was when the album ended.

—David W. Pritchard