#448: The Police, "Synchronicity" (1983)

I know a thing about obsession, and the kind of love a person should be embarrassed to admit to. I know about being eviscerated, those selfsame rhythms, offering myself up again and again. I know a thing about confession.

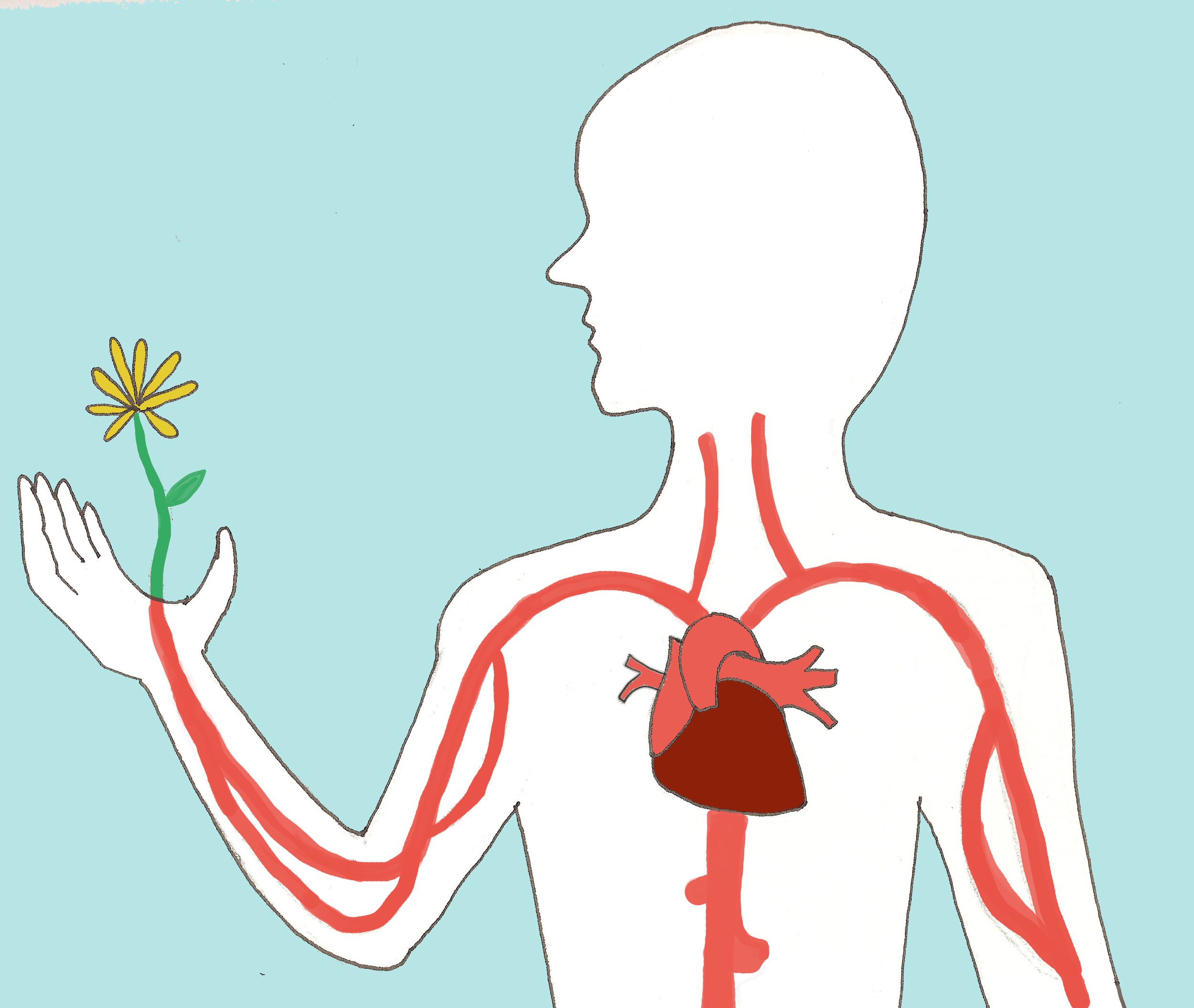

A couple weeks ago, I stayed up with someone I love, and when it got late enough, the snow that was supposed to come started falling. We watched it caught in the porch light through his kitchen window. I stood in front of the table by the window and he stood beside me, and we didn’t touch and neither of us spoke, and what I felt in that moment was the most tenuous sort of awe, at how perfect that moment was, and that night, and how sad it was that it would pass. How sad, how sad: all the things we cannot keep.

“Every Breath You Take” is one of the first songs I remember being confused by. I couldn’t figure out if it was romantic or unnerving, and I got the feeling, as I listened, that the singer should be embarrassed by the force of his desire. It seemed, certainly, like a love song, but not one I’d like to have sung to me, or one I’d like to sing myself. I couldn’t tell if we were supposed to identify with or feel sympathy for or pity or fear him—the answer, I realize now, is yes. Yes and yes and yes.

When we write, when we create, we both are and are not ourselves. We could never fit all of life onto a page or into a song: tensions are identified, amplified, and a character is built, and an arc is chosen, and then the art takes on its own dimensions and its own identity. We understand: love, sometimes, makes stalkers of us, and this is the story of the song but it’s not the whole story.

Last night, I smoothed his hair across his forehead, and very, very softly, I insisted: You can’t hurt me anymore, when you say you don’t want me I simply won’t believe it.

I know this is, in some ways, deranged, but is it not also human, to sometimes be unhinged by the strength of one’s own feeling, and what is love if not a kind of faith, and is there anyone who truly knows where lies the line between faith and delusion?

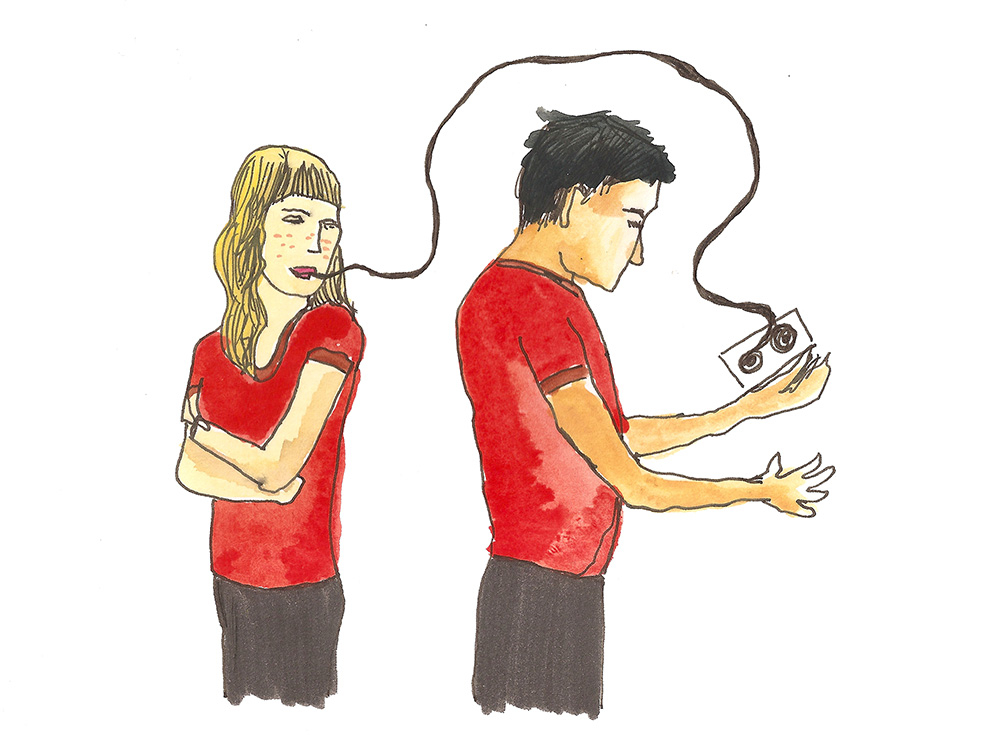

Illustration by Annie Mountcastle

I spent a lot of time wondering about love before I ever loved anyone, and I’ve spent a lot of time wondering about love after having loved, and I spend a lot of time wondering about love when I’m in love, and when I think of people, of human nature, of the grief and the solace at the center of our lives, I think of love. I wonder if this is absurd. I wonder if this is a character flaw. I wonder why it is, that I’ve always seen the world like this: there is the love, and there are the things we do to fill the space around and between the love. It is the love that pains us, but it is the love that makes us whole.

I want to apologize for my romanticism; this is how I’ve always been. My happiness is unbearable and my loneliness is unbearable and my boredom is unbearable, and sometimes I hate my own extremism, my dramatics, my sensitivity, my inability to maintain an even keel—but it is, mostly, I think, a blessing, to feel so much. To be vulnerable and to be alive.

I wonder, even now, if I’m misreading the whole thing—if I identify with the song but shouldn’t, if I feel a pang of recognition at that ugly sort of desperation that I shouldn’t feel or, if I feel it, admit to. But we all hold within us some ugliness and some desperation and a good deal of fear, and there is comfort in that, I think, to identify with one another through our imperfections. And it’s a good thing, the art that unnerves us because we recognize our own flaws within it. That community is a comfort: if we must sometimes be ugly and desperate, we must sometimes be ugly and desperate. Let us admit it. And so we forgive ourselves, and forgive the ones we love, and forgive the world for its difficulty and forgive our lives for their countless imperfections and we go on and on hoping for the best and the good things come and the bad things come and the good things come again.

—Katelyn Kiley