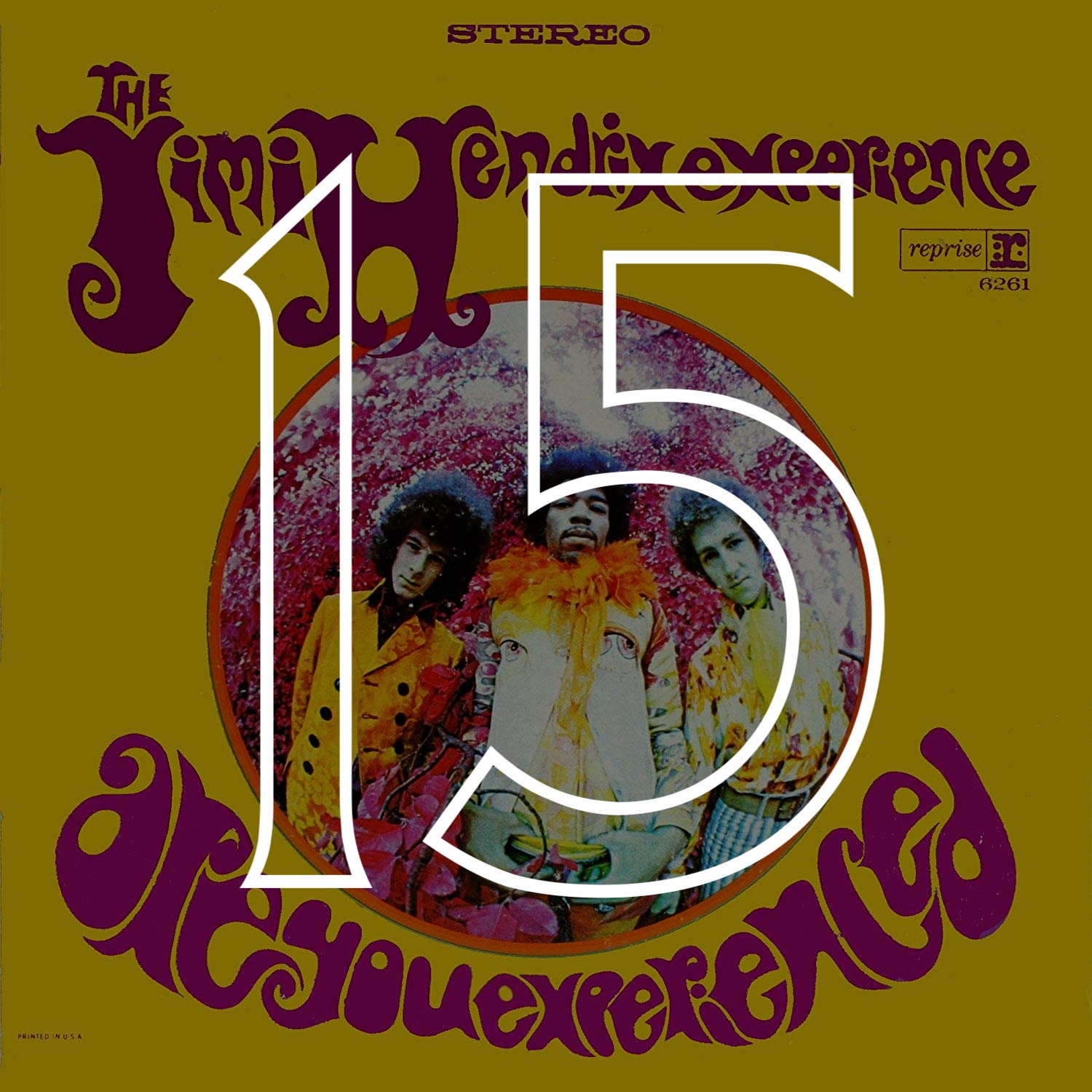

#15: The Jimi Hendrix Experience, "Are You Experienced" (1967)

I need to see him there, the boy huddled in a motel closet, shielding his eyes from the slatted light. Beyond, Al and Lucille: stumble-drunk, accusatory, shoving. Soon the sound of blows, a body flung across the rickety bed, a cheap lamp’s muffled crack like a firecracker bursting in a bottle’s throat. Maybe the boy stares into the carpet stains and makes of them a cosmos. Maybe he just weeps into the dust. Wherever his four younger siblings are—scattered with aunts, back in foster care—he’s glad they are not here. Here, a boy hunches into his knotted hunger and strums the bristle broom draped across his lap. At eight, he’s learned a truth some never learn, which is that our damage breeds something worse than fear: it is the terror we carry into our survival. Inside each self are the strangled selves that didn’t make it. Even now he hates the sound of his own voice, mumbly and coarse, how it strains to find a note and keep it. The story should begin with a boy jailed in screams. Who fills his ears up with himself. Who leans into the closet dark and hums.

*

Jimi Hendrix is where hyperbole goes to die. A half-century after his death, his legacy is an endless and insufficient heaping of glory. Greatest guitarist of all time. The sixties’ most tripped-out groover. Our Black Picasso. Sex symbol. Rebel. Icon. I don’t know much, but I know Jimi would have lapped this up, grinning. After being the neglected afterthought of his parents’ failure, an army washout, and a broke sideman for nearly a decade, what guy wouldn’t? Hendrix perfected cool, which might be best defined as the practiced air of not giving a shit, even though deep down, you are totally giving a shit. Unlike Dylan, who continues to court a mystery cult to offset the obviousness of his limitations, or Jim Morrison, who simply crumbled under the weight of his own pomposity and alcoholism, Hendrix took us by raw force of talent. He was a genius, he knew it, and he recorded the most visionary music of the 20th century in less than four years. He may have camouflaged his insecurities with swagger, but beneath the peacock blouses and burning Fenders, he knew his quarrel was with the universe. Can you imagine what an incomprehensibly liberating and lonely burden it must be, to be the best alive? Consider that Prince, the most gifted and prolific artist of his generation, basically spent his entire career trying to out-Jimi Jimi. And here we are, in their long shadows, rocking as we grieve.

*

The Beatles’ catalog aside, is there a more mythic rock album than Are You Experienced? For those of you who didn’t waste your teen years worshipping at the altar of psychedelia, let me give you the Spark Notes version. After years of toiling as an itinerant hired gun for the Isley Brothers and Little Richard, Jimi Hendrix is “discovered” in 1966 by Linda Keith—Keith Richards’s then-girlfriend—who quickly becomes the guitarist’s confidant and cheerleader. Enter Chas Chandler, former member of the Animals and aspiring producer, who hears one Hendrix set in Greenwich Village, whips up a contract, and flies his new star to London where the Jimi Hendrix Experience is hastily assembled as a power trio to showcase Jimi’s unprecedented pyrotechnics. The frenetic Mitch Mitchell joins on drums, and rhythm guitarist Noel Redding makes the switch—with uneven results—to bass. In less than nine months, from late September 1966 to May 1967, Jimi Hendrix signed with a label, moved to a new country, formed a band, began songwriting in earnest, proved his prowess in the studio, flabbergasted the entire British rock scene, and released his first album to rave reviews. He did this while simultaneously transgressing boundaries of race, culture, and class, which would have otherwise maintained his invisibility forever. The tired platitudes we typically ascribe to albums like Are You Experienced—groundbreaking, ahead of its time—don’t come close to articulating this kind of sudden historic arrival. With a modest budget and a timid, under-rehearsed rhythm section comprised of two English guys who were essentially strangers, Hendrix made, in eight weeks, an album that would obliterate most bands’ greatest hits. At turns incendiary and lyrical, his playing on these eleven tracks was, and remains, the proverbial throwing-down-the-gauntlet for every guitarist who dares plug in after him. And yet, Jimi’s artistic range should ultimately endure as his greatest legacy. Sure, “Purple Haze” and “Fire” offer archetypal machismo, but “Hey Joe” demonstrates Jimi’s gifts as an intuitive arranger of others’ work, so much so that few remember it is a cover. (This happens again two years later, when his recording of “All Along the Watchtower” makes Bob Dylan forget Bob Dylan wrote it.) “Manic Depression” and “Love or Confusion” may be the earliest examples of popular music interrogating the messiness of obsession and mental health. “Foxey Lady” is sexiness personified. And for those of us who view Hendrix as a poet, “May This Be Love” and “The Wind Cries Mary” are among his most introspective, ethereal ballads. It must have seemed like braggadocio in the spring of 1967 when prospective buyers skimmed the rear sleeve of Are You Experienced, which claimed the album breaks the world into fragments, then reassembles it. Bless that writer, unnamed and underpaid. They got it right.

*

Hendrix learned how to play guitar with his teeth before he ever dropped acid. If we’re going to have an adult conversation, which I regard as the only kind worth having in a nation bloated with hype and bullshit, then we need to talk about Hendrix’s substance abuse. Was Jimi a junkie by the end? Probably. Did he record hundreds of songs and tour the world in a strung-out daze? Hardly. While the recording of Electric Ladyland, his final studio achievement, ultimately became a Warhol-esque orgy that racked up six figures in debt, ran over schedule, and took on all the trappings of excess, for most of his career Hendrix was the kind of musician who arrived early, stayed late, and remained ferociously perfectionist. At seventeen, aroused by the titular song’s cheeky reference to tripping, I believed that adolescent nonsense about exploratory drug use serving as a gateway to transcendent inspiration. Now, in middle age, I suspect that Jimi’s steady flow of dope and booze (and Scandinavian models) was his only—if dysfunctional—means of coping with the crippling artificiality of the music industry. Electric Ladyland became a masterpiece because each time the party ended, Jimi nudged the mics and tweaked the nobs and cut another take. Similarly, Are You Experienced endures as the most authoritative debut in rock history because after twenty years of rootless rambling, a poor kid from Seattle resolved to fly across an ocean, knowing his country couldn’t hear him yet. I once had a high school teacher snarl at me and say someday you’ll realize all that stuff you worship is just about drugs. He was an asshole. If he’s still alive, I hope he’s slowly suffocating in his bitterness. Only in America could we conflate our self-destruction with our dreams.

*

Reportedly, when Hendrix, who was one-fourth Cherokee, first saw the sleeve design for his second album, Axis: Bold As Love, with its psychedelic swirl of Hindu iconography, a laborious and extravagant cover that cost his label $5,000 ($36,000 today, calculated for inflation), he simply sighed, I’m the other kind of Indian. Like most people of color, Jimi was woke before we had a word for woke.

*

They get the guitar wrong. Perhaps you recall Pepsi’s 2004 Super Bowl ad, where Jimi Hendrix is a doe-eyed suburban kid who, after a sip of the aforementioned soda, hears the opening riff of “Purple Haze” roaring in his head. Out of my many grievances with this objectification, the wrong model of guitar belongs low on the list, after they depict the mid-1950s as serenely post-racial and they fictionalize an adolescent Jimi as leisurely middle-class and they butcher the poetry of a poor boy pulling a one-stringed ukulele out of the trash. Even still, I cannot abide the aching irony that the Fender hanging in the commercial’s idyllic pawn shop window is a Telecaster, an instrument Hendrix played sporadically (if at all), and not a Stratocaster, his signature axe that he popularized the world over. Since the marketers aren’t worth it, I’ll spare us an even more savage Freudian reading of this premise, which might begin with the topic sentence Pepsi unwittingly pitches their sugar poison as a gateway drug. Imagine the boardroom fogged with aftershave where young executives, all Jared Kushner lookalikes, walked through the storyboard for this dross, smug and self-assured it was cool. Imagine their salaries, their Jaguars, the walls of glass that separate them from the custodians who wipe down their cubicles. Imagine them at their rooftop soirees, tipsy after two microbrews, trying to impress each other’s women as they strum haltingly through a Dave Matthews number. Their sunsets are bonfire orange. Their coolers are full. They harmonize through perfect teeth.

*

I need to see him there, the sophomore with a head cold, drunk on screwdrivers, surrendering to night. Stacked beside his dorm desk are a dozen inter-library loans on Jimi Hendrix for a term paper he isn’t qualified to write. The sentences he’s pecked since dinner are forced, disjointed, overwrought: Band of Gypsys at the Fillmore, black power trio as black power statement, “Machine Gun” as magnum opus against Vietnam. His only hope to finish school is a third and final year of overloads. His meal plan is running out. A Goodwill turntable sizzles down the hours. He’s learning the terror of reducing a thing you love to an assignment. He’s learning some stories aren’t his to tell. Outside, he sparks a Parliament and watches its smoke arabesque into Pennsylvania snow. When he shuts his midnight eyes, he can feel the flakes drift down the gap around his jacket collar. He’s going to stand there a long time, leaning on a lamppost, humming at the storm.

—Adam Tavel