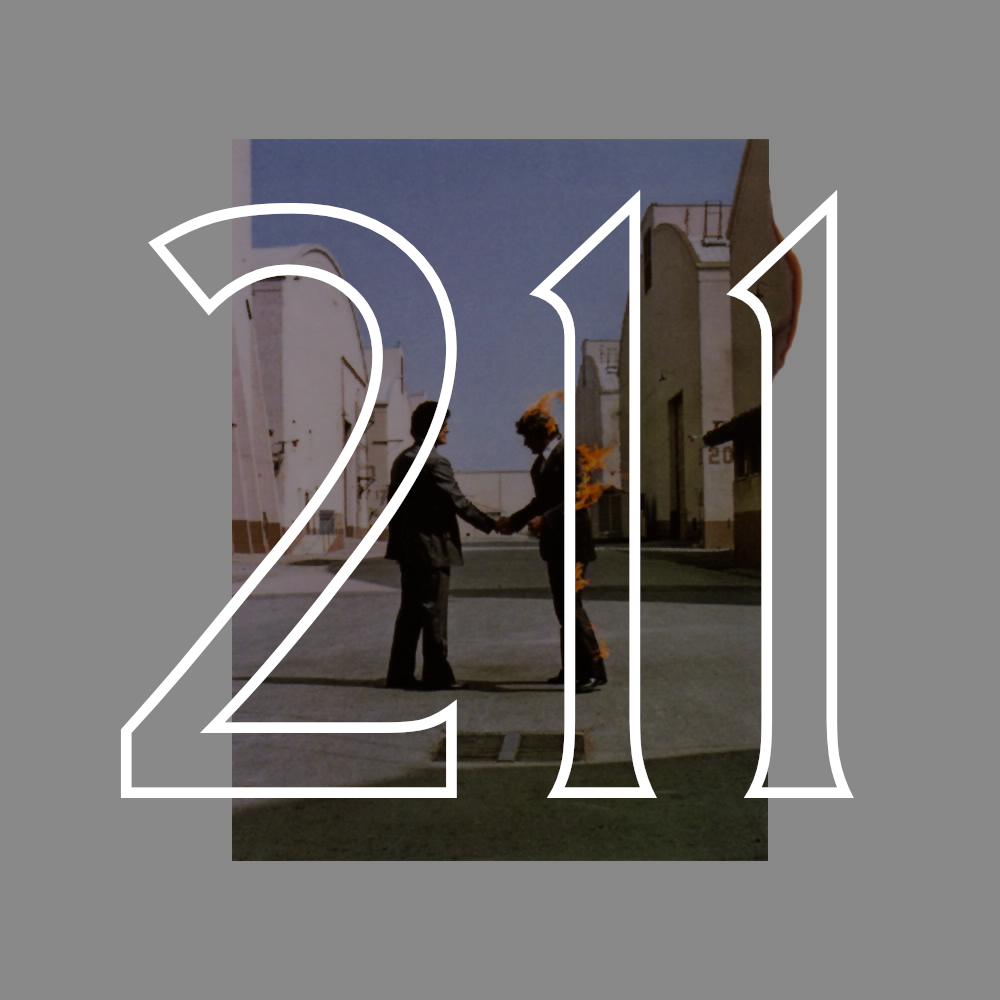

#211: Pink Floyd, "Wish You Were Here" (1975)

Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here is an album about absence. About subtraction. It’s about the things we lose and the ways we lose them. It’s about losing Syd Barrett to the doomed combination of drugs and mental illness. It’s about a band losing its soul to the doomed combination of success, label pressures, and outlandish egos. It’s about losing connection and authenticity. It’s about losing, losing, losing.

And so this is going to be a story or essay about subtraction. Or maybe it’s going to be about subtraction through addition?

You see, because there was a breeze, and then a steel breeze, and then no breeze, and Syd was gone.

Just like there had been the album’s cover models, Ronnie Rondell and Danny Rogers, and also Ronnie Rondell’s mustache and eyebrows, and then there was fire—applied to Rondell’s clothing like makeup, like paint—and then there was the pose for the photographer, and then there was wind, and then Ronnie Rondell’s mustache and eyebrows were gone. Subtraction through addition—add fire to wind and a man loses his hair.

And there’s something to learn there, something we should probably understand—what is it? Don’t let someone set you on fire? Is that too easy?

But see, it wasn’t just Syd. And it wasn’t just Ronnie Rondell’s mustache and eyebrows, because not long ago, there was a breeze, and then a steel breeze, and then no breeze, and you were gone.

But let’s not make this about you. This is about Pink Floyd’s album Wish You Were Here, which, as it happens, is an album I came back to after you were gone, is an album I came to understand in new ways after you were gone. It stopped being the Pink Floyd album about Syd and the record industry—those are just the album’s framework, not its big ideas.

Or maybe I’m finding license in loss to give Pink Floyd more credit than they deserve.

*

Let’s talk about Syd for a minute, and the way that Pink Floyd lyrics, whether written by Roger Waters or Polly Samson, always drape him in light. The opening lyric of “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” is “Remember when you were young / you shone like the sun.” Then, of course, there’s the song’s title—Syd is a diamond that shines, and we know it’s about Syd, even without having to read the lyrics, because the song’s title tells us it’s all about Syd:

Shine On

You Crazy

Diamond

Of course, almost two decades after Wish You Were Here was released, on “Poles Apart,” one of the few decent post-Roger Waters Floyd songs, David Gilmour would sing words written by his wife, Polly Samson: “Why did we tell you then / You were always the golden boy then / And that you’d never lose that light in your eyes?” Even on “Brain Damage,” the immortal penultimate track from Dark Side of the Moon, when Roger Waters sings, “And if the cloud bursts, thunder in your ear / You shout and no one seems to hear / And if the band you're in starts playing different tunes / I'll see you on the dark side of the moon,” perhaps alluding to Barrett through thunder and darkness, there is the implied light of the lightning that accompanies thunder, and the implied light of the sun reflecting off the non-dark side of the moon. What does it mean that all of these lyrics compare Barrett to light? I don’t know—maybe it’s just an extension of several clichés about shining bright and burning out. Maybe it has something to do with the time that Syd set his own head on fire during a gig at UFO. Or maybe that’s all too literal.

*

There is another light I remember, too, and it wasn’t fire, and it didn’t burn atop Syd Barrett’s head, and it didn’t singe off Ronnie Rondell’s mustache, and it didn’t come from the sun, or a diamond, or from eyes, and it didn’t come from a bulb, it came from you, but it’s gone now, so what does it matter?

I don’t know what was added that took you away. Maybe this is just a story about subtraction for its own sake.

*

Inside the sleeve for Wish You Were Here, because that’s what I’m really talking about here, that album, not you, there is the red handkerchief blowing on a breeze—we don’t know if it’s a steel breeze or not, but it probably is. Because the image is a static photograph, we can only infer movement from the object’s relationship to its surroundings. Its motion is absent. Same with the diver in another of the album’s interior pictures: his body breaks the water’s surface but there is no splash, no ripple—the water appears undisturbed. The question: where is the absence here? Are the waves and ripples the absent things? Or are we meant to infer from the lack of splash that it is the diver who is absent? What I’m getting at: was Syd the water or the diver?

Are you the water or the diver?

Another question: why am I still writing about you in present tense?

There were other famous images on the album’s outer sleeve—the two men shaking hands, one on fire (and recently relieved of all the hair on his face), and the back-cover businessman with a flat, skin-colored cloth for a face, and without wrists or ankles—an empty suit. A bit on the nose, for sure. But here is more of that subtraction by addition. Add success, add fame, add money, and money, and money, and something will be lost, something for which we can name symptoms, but never the thing itself. Maybe Wish You Were Here is a bit heavy handed with its symbols, but this is something people can relate to. We grow up, get or don’t get old, make or don’t make money, incur or don’t incur debt, and everything becomes about money and debt until something is lost—subtraction through addition and subtraction and/or addition and probably a little more subtraction. And Wish You Were Here is right about that—the structures in which we live alienate us from ourselves and those we care about. Sorry if that’s all a little didactic, a little on the nose—but c’mon, we’re talking about Pink Floyd here.

*

In the years after Wish You Were Here was released, Pink Floyd would continue a slow dissolution that began with the success of Dark Side of the Moon and also, coincidentally, around the same time they introduced Mr. Screen to their live shows—that flat circle, like time itself, on which lights, movies, lasers would shine. A few years after the fact, touring behind their album Animals, Roger Waters would spit on a fan at a concert in Canada—a Canadian!—and then he would make The Wall, which is like Wish You Were Here turned up to fifty, like if Wish You Were Here is a little on the nose, The Wall is up to its elbows in the goddam nose. And let’s be honest—Animals isn’t a walk in the park either. Roger Waters was angry, and his art with Pink Floyd was about that anger, about his alienation. About losing Syd. About being afraid of losing himself.

And therein lies a, or perhaps the, fascinating truth about Pink Floyd: their story is Syd Barrett’s story. Their greatest, most beloved albums all, in some way, tie back to Syd. Except for maybe Meddle and Animals. But the big albums, the ones on the lists, the ones in every dad’s CD collection—those all come back to Syd.

*

But let’s forget about Roger Waters and Syd Barrett for just a second, because this is more important: One night in December, there you were in my car, drunk and almost crying on the way home from the bar. You were lonely, you kept saying. When would you find someone? Why did nothing ever work out for you? And I remember the way your voice broke. And I remember the green x-mas laser lights blasted across your dad’s garage. And your flight left the next day so when I pulled into the driveway, I got out of the car to hug you and you slipped on a patch of ice, but didn’t fall, and then you told me we’d talk soon. Told me you’d have a safe trip back. And then you slid under the half-raised garage door and I never saw you again.

You were here, and then you were there, and then you were gone, and now there is a park bench dedicated in your memory. This is not subtraction through addition. The park bench came after you were gone. This is subtraction, and subtraction, and subtraction.

*

During the production of Wish You Were Here, there was Roger and there was David, two men in the studio, their band starting to unravel around them. Following the somewhat surprising (to them anyway) success of Dark Side of the Moon, and before making Wish You Were Here, that band worked on an album called Household Objects, on which all of the arrangements would be performed, not on instruments, but on, well, household objects—an absence of instruments. We’ll call it subtraction through subtraction. But that didn’t take and the band began work on a set of songs that would eventually become Wish You Were Here and Animals.

And then there was Roger and there was David, both in the studio, both looking for an idea, and then there were those four notes, simple and easy, slow and pure, pouring like a molten steel breeze from David’s guitar:

Shine On

You Crazy

Diamond

Now, a little bit of music theory about those notes, found on the internet:

By the end of the phrase, the listener’s tonal ear is confused: what key am I in?”

And there was Roger, and he heard something in those four notes—perhaps their disorientation, their ambiguity, their uneasiness, their questioning—that made him think of Syd.

Not long after, as the band was either finishing up or listening to playback of “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” who should wander into the studio but the man, himself,

Shine On

You Crazy

Diamond.

Until that moment, despite having been haunted by his presence for years and albums, no one in Pink Floyd had seen Barrett for seven years. But there he was, as if conjured by Gilmour’s haunted guitar lick, a ghost, traded for a hero, traded for another ghost, head and eyebrows shaved, far heavier than he used to be, wearing a white trench coat and white shoes. When someone in the studio asked him how he’d put on so much weight, he said something about a big refrigerator full of pork chops.

Fuck.

Subtraction, subtraction, subtraction, subtraction, subtraction. And a little bit of addition through pork chops.

*

I try to think of four notes that might conjure you. It couldn’t be the same four notes, couldn’t be the same song.

To try to conjure you with “Shine

O

N

You Crazy Diamond,” would be theft of an egregious order.

That one belongs to Syd. And anyway, even though Syd wandered into the studio, he was never back. Though he asked if he could pick up a guitar and play on the track, he would never play with Pink Floyd again. All Gilmour’s guitar lick did was summon a ghost, minus eyebrows and hair (and without the help of fire, even, as far as anyone knows), plus a belly stuffed with pork chops. As math, it might look like this:

Ghost - Head & Eyebrows + Pork Chops = ∅

And I know there’s something to learn in that, but I’m still not sure what it is.

—James Brubaker