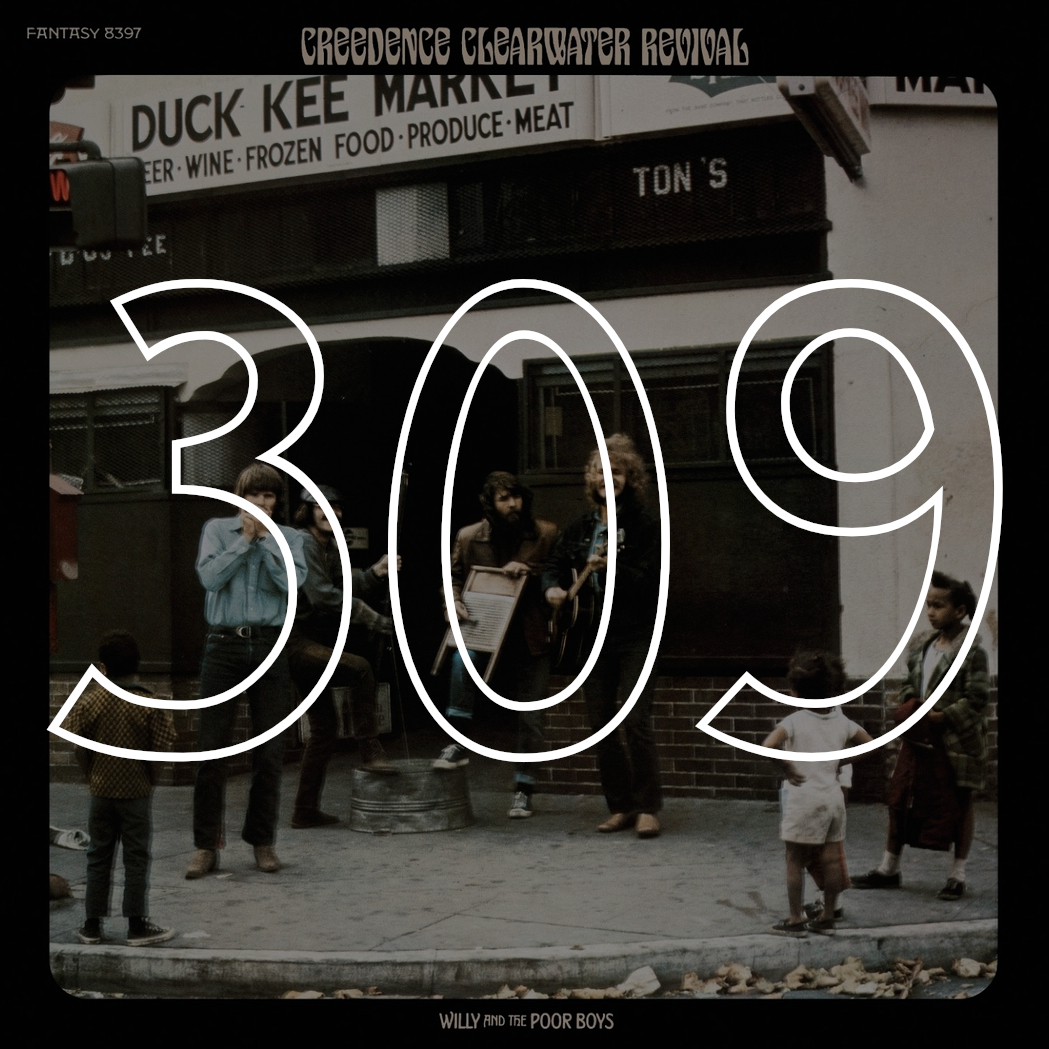

#309: Creedence Clearwater Revival, "Willy and the Poor Boys" (1969)

Willy and the Poor Boys is a strange album. It boasts two instantly recognizable hits—"Down on the Corner" and "Fortunate Son"—the latter of which seems to be the very archetype of the North American antiwar rock song of the 1960s and 1970s. But these two songs persist, not solely because they are transcendent works of art, but because ad campaigns (for Walgreen's and Wrangler jeans) have used them in ways that fully neutralize their protests. The inversion of the content is so neat, the irony so precise, that one would be forgiven for thinking a prize-winning novelist named Jonathan planned the whole thing as an allegory for the way that mass culture degrades and thwarts human experience. These songs are the information we have from the outset as we approach Willy and the Poor Boys, which makes things a little more like a detective story than a prize-winning novel by a guy named Jonathan. They are isolated snippets of information that we gradually come to understand as part of a larger, dynamic unity. Except we end up, not with a crime, but with an expanded view of the tone or feeling of protest that attended our Jonathanesque cynicism in the first place.

In fairness to cynicism, I am a little bit cynical. I think it's important to be, at least to a certain extent. There's no way to will away the truth of the culture industry, which is precisely that you can use a song that sneers at the American ruling class for blithely perpetuating imperial war to underscore the "Americanness" of blue jeans made in sweatshops on the other side of the globe (it's worth noting that we went to war in the first place to make sure that reserve army of labor was secure). But I don't think that this means protest is cheap, short-lived, or pointless: far from it. In art as in life, I cannot think of anything more important than protest. I would love to bring back another beautiful p word, propaganda, to designate this feeling in the cultural sphere. But it ultimately doesn't matter what we call it, so long as we concede that, no matter how co-opted or contained or dehisced from its initial foment it has been, this feeling persists, it agitates, it expresses a desire to somehow remake the world. And we should be heartened that the culture industry has to resort to selling us knockoff Utopian knickknacks because it can't deliver on any of the promises it makes, and it knows it, and it knows we know it.

Heartened, but not triumphant: this is how I would characterize Creedence Clearwater Revival's performance on Willy and the Poor Boys, which seems to protest against an inculcated cynicism as much as it does against the government. The result is a potent ambivalence that furnishes an expansive way of seeing. The album begins, in "Down on the Corner," with people flocking into the streets; it ends, in "Effigy," with the burning of an effigy of something extraordinarily big. Are the people who take to the streets to dance at the end of the working day, outside a courthouse no less, the same ones who watch something gigantic burn to the ground by album's end? And what of those who can't pay the buskers, where do they stand on effigy-burning? What does a group of people really want: a dance party or a mass movement? what's the difference between the two? when does the line begin to blur?

Expansiveness is not just a matter of bodies accumulating in the streets. It also factors into how CCR figure the relationships between core and periphery, or urban and rural spaces. "It Came Out of the Sky" begins with a farmer in Illinois ("just outside of Moline," sings Fogerty) and ends with Hollywood, the Vatican, and the White House all clamoring over what to do with the UFO that plops in that farmer's field. Eventually the farmer refuses all summonses and offers and says he will sell the UFO for seventeen million dollars. A little later, in "Feelin' Blue," the speaker laments that his time has come, but gives no real indication of in what sense he means this, only that he must be moving on. Has he been drafted? Has he lost his job to offshoring? Both seem reasonable responses, especially given the direction we receive to "look over yonder" in the lyrics. Both would certainly result in the feeling that gives the song its name and its refrain. But then for all that the music is flippantly upbeat, a mid-tempo affair that concludes with a call-and-response of sorts between the vocals and the guitar. It is as if the ability to sing and to play intervenes against melancholy, or at the very least prevents sadness from hardening over into melancholy.

All this comes to a head in "Fortunate Son." The song's refrain, like that of "Feelin' Blue," seems to revel in the capacity to make distinctions in language, but now there is a more explicit political edge. "It ain't me" derives its power from its negativity, which ends up being the more expansive way to chart solidarity than any kind of affirmative mode. There are a lot of us who are not millionaires, senators' sons, fortunate ones, etc., just as there are a lot of us who are expected to fight for the benefit of the ruling class, who profits from but does not suffer in war. To see in those terms is to see in terms of collectivity. It is to grasp the scope of who might be showing up to dance in the street in "Down On the Corner." And it is to recognize that the people who have cannon pointed at them during "Hail to the Chief" vastly outnumber those who pay for and fire the guns. But in this there is a final, tragic ambivalence: the class with the cannons—in 1969 as today—are the ones who do the killing, even as they blame the people they shoot at for perpetuating bloodshed. Willy and the Poor Boys has no solution to this problem, but it tells us where we can find one: down on the corner, out in the street, where the cynicism of the prize-winning novel finds itself transformed into a refusal so big it could swallow the whole world, or at least burn it in effigy and build something more beautiful out of the ashes.

—David W. Pritchard