#74: Neil Young, "After the Gold Rush" (1970)

At fourteen, I am a band-T-shirt-and-black-eyeshadow wearer, shuffling in my Vans and enormous JNCOs at my local junior high. It is spring of 1999, a strange time: only a few weeks after the Columbine shooting, which has made everyone look at me suspiciously, edging away from me in the halls. The stares that have always been there are of a different quality now, and make me self-consciously adjust the neon plastic barrettes in my magenta hair. At a routine appointment, the dentist I’ve had all my life pointedly asks me if I intend to shoot up a school.

But at fourteen, I found solace at the mall, where I met up with friends who looked like me, and felt most welcome loitering in a Hot Topic. The scent of unburned sandalwood incense and baby powder and something unidentifiably candy-sweet wafted through the store as my friends and I would window shop for merchandise we could rarely buy. Sometimes we coveted clothing, or jewelry with glittery or spooky motifs, but it was almost always music.

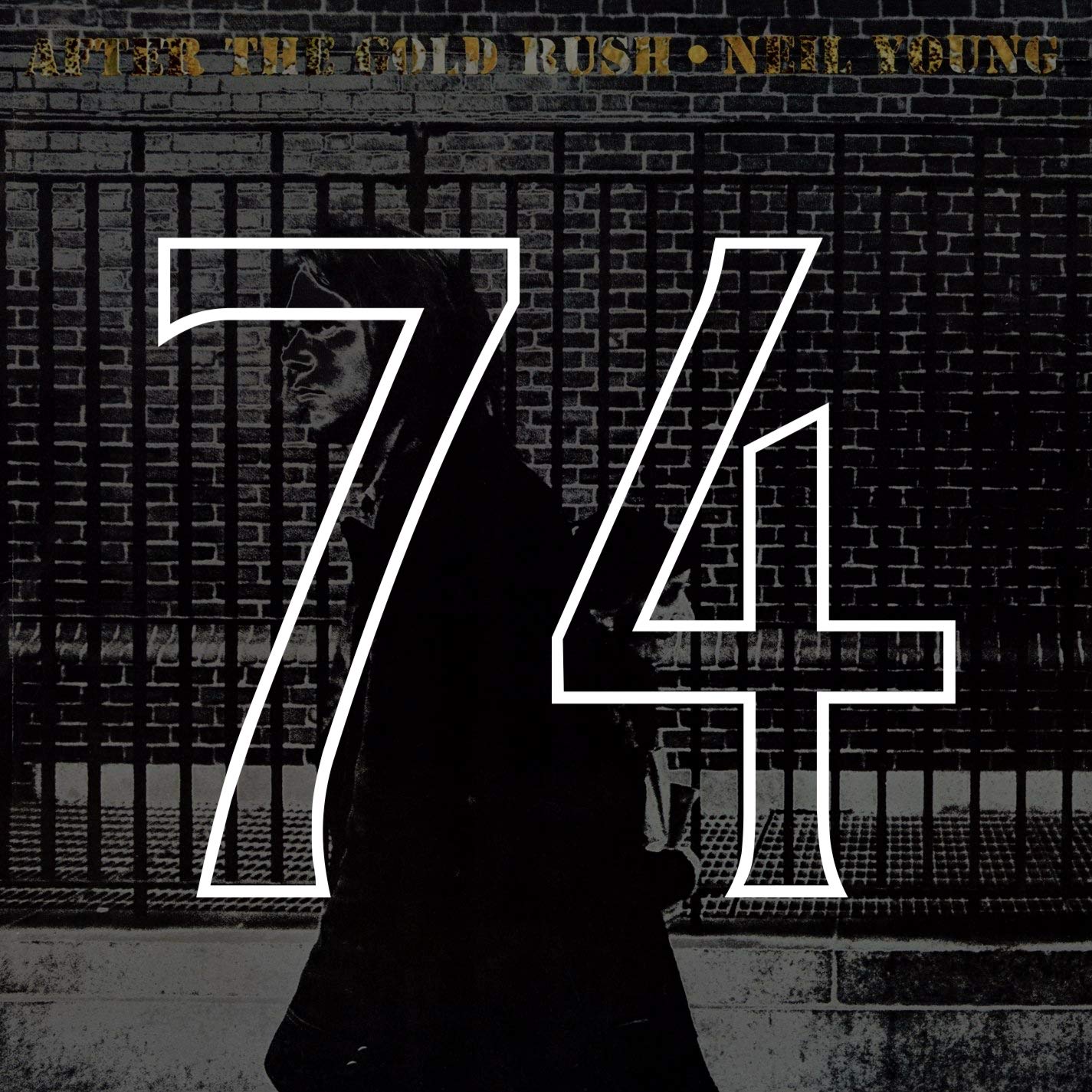

I noticed, too, that the store had started stocking more LPs alongside the CDs. I don’t remember exactly how it transpired, only that I ended up with a clunky stereo from the ‘80s with a turntable on top, which was purchased from an ad in the paper. I especially loved the knee-high speakers we bought with it, that could seemingly blast away even the worst day of 8th grade. But I had very few records of my own to play, at least until I could start working in the summer. Something possessed me to start pilfering my parents’ from the shelf in the basement. I noticed After the Gold Rush, with its gloomy, grainy black-and-white cover, and deemed it promising: it didn’t look too suspect on the outside, at least. If any of my friends found tame, boring music in my room, it would be the end of my social life. Deep down, I must’ve known that these unspoken rules about what made something “cool” were not all that different from what the popular kids lived by; if I was truly free to be myself, I wouldn’t care. Still, I trekked upstairs with some trepidation, feeling like I was betraying something, defecting from my side.

The opening track, “Tell Me Why,” to my 14-year-old self, made me picture people singing around a fire at a sleepaway camp in the 1960s. The acoustic guitar was so clean and cheery, one could clap or tap a foot along without much practice. The vocal harmonies channeled something almost angelic. It evoked landscapes of sunny fields, forgotten times. All of this was a far cry from the drop-D tuning and distortion, the overt aggression and bluntness I was accustomed to. I slid the record back into its sleeve, and tucked the album covertly into the rest of my collection, between Dead Kennedys and System of a Down, and hoped no one saw it when they came over.

That summer, I woke up at six o’clock each morning to work on a tobacco farm, as my parents and grandparents, and most young people in my town, had done for generations. For ten weeks—or however many we could handle—we’d work eight hours a day, Monday through Friday, picking and drying tobacco leaves that would be used for high-end cigar wraps. I was excited: it meant I could spend my own, hard-earned money on music and clothes, and cheese fries at Denny’s with my friends.

Every morning, I walked about half a mile to the nearest major intersection in the early light, where I would wait with my lunch bag to be picked up by a decommissioned school bus painted blue. Everyone wore their most beat-up old clothes, myself included, meaning I could usually pass as a “normal kid” if my hair was tied back. It was strange stripping myself of the thing that felt so central to my identity at the time. We all looked the same, groggily boarding the bus that would carry us teenagers from our suburban neighborhoods, across the Connecticut River that divided us and the next town over, a farming community known for its great school district.

The bus wound down the dirt roads between the fields and belched us out near the barns. The family who owned the property then barked orders, and assigned our work for the day in small groups. A lot of us working at the tobacco farm were around my age, or a little older: mostly high schoolers, a population I’d be joining in a few months. Already in the fields when we arrived each day were the migrant workers, all from Jamaica or elsewhere in the Caribbean, who lived on the property in tiny, run-down cottages. They would spend the summer, and return home at the end of the season, preceded by the weekly wire transfers of their checks supporting their families. There seemed to be a significant number of these workers, and yet, oddly, I felt like I hardly saw them: they always seemed to be working elsewhere, off in a different section of the field, concentrated in one corner of the barn. We never spoke to them.

The work was grueling and grotesque. It was July, and the heat was brutal; some worked out in the fields, directly under the sun—but I was lucky, and assigned to work in the sheds, which provided shade but not much else. Here, the broad, green leaves would be strung up on wooden laths with the aid of a pre-war contraption. With one leaf in each hand, we’d jam the thick stems up into a serrated blade that would thread a string through them, allowing the leaves to be hung and dried. Speed was a priority, and more than one kid was sent to the hospital because the blade went through their thumbs. The dirt floors of the barns were a fine, loose powder that would whirl up and land in our eyes, or mix with the sticky tobacco juice that dripped down our wrists, making a mascara on the hair of our arms.

The rafters of the barn were filling with leaves in varying stages of drying, acting as insulation that held in the summer heat. The air smelled like stale, unlit cigarettes. I was covered in filth and sweat, my biceps burning from the repetitive motion. I began complaining loudly about my misery. I was slowing down, clumsy with exhaustion, and not treating the leaves delicately enough; ripped tobacco leaves were useless. If anyone important came by, I surely would’ve been yelled at. I whined about just needing a break, which I knew would not be granted. One of the migrant workers walked over to my staton without a word, and began sewing my leaves for me. He was totally calm, and moved with a fluid efficiency that I could hardly fathom. With the exception of the trickle of sweat snaking down his dark neck, his work looked effortless. I watched silently, unsure of what was happening. Why was he at my machine? He finished three laths of work, just over a minute, then met my eye, nodded, and returned to his own machine across the barn. I managed a “thank you” a few seconds too late.

This moment happened almost 20 years ago, and yet it’s a memory that resurfaces often. I am left wondering now, as an adult, was this a gesture of kindness, because I was so young and a girl and the work was truly strenuous—or did he just want me to shut up and stop whining? Was his stoic silence in doing my work unprompted something symbolic that I’m still not sure I understand? I think of this moment most whenever I hear “Southern Man.” The obvious racial element, as well as the setting of a tobacco plantation perhaps makes for a facile observation. But this moment happened just shy of the 21st Century, several states north of the Mason-Dixon, and yet there was no scathing song critiquing the region I grew up in. Growing up, it was easy to criticize other places and pretend, with our cable TV and my bedroom full of cheap clothes and toys, that the truly distressed and backwards places were elsewhere, in geography and history. Meanwhile, a family in a picturesque New England town was bussing in children from the less desirable suburb across the river, and housing black international workers in “little shacks” to support their carcinogenic agribusiness.

One of the things I have grown to enjoy about After the Gold Rush is its understatedness. The almost-waltzy “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” is deceptively, well, heartbreaking. The pain is all the more evident in its subtlety. The jubilance I thought I first heard in “Tell Me Why” is tempered with lyrics about alienation and hardship. Young’s voice is often characterized as “whiny,” even by a number of his fans. But it’s not quite true: it’s more urgent, mournful, exposed; at his highest pitches (in songs such as “After the Gold Rush” and “Don’t Let It Bring You Down”), his voice reads as almost a whimper, a plaintive insistence at singing a line that seems nearly too painful to voice. “I Believe in You” is haunting in its slow-brewing gloom. Young is sometimes pegged as the “Godfather of Grunge,” and only just recently have I come to believe it: the darkness evident in these songs is palpable to the careful listener—something I was not at 14. At that age, I would sometimes find the smooth gap between the grooves on the record, gently dropping the needle down from between my black-polished nails, and listen only to “Southern Man,” the song with the plainest message, the loudest guitar.

—Lisa Mangini