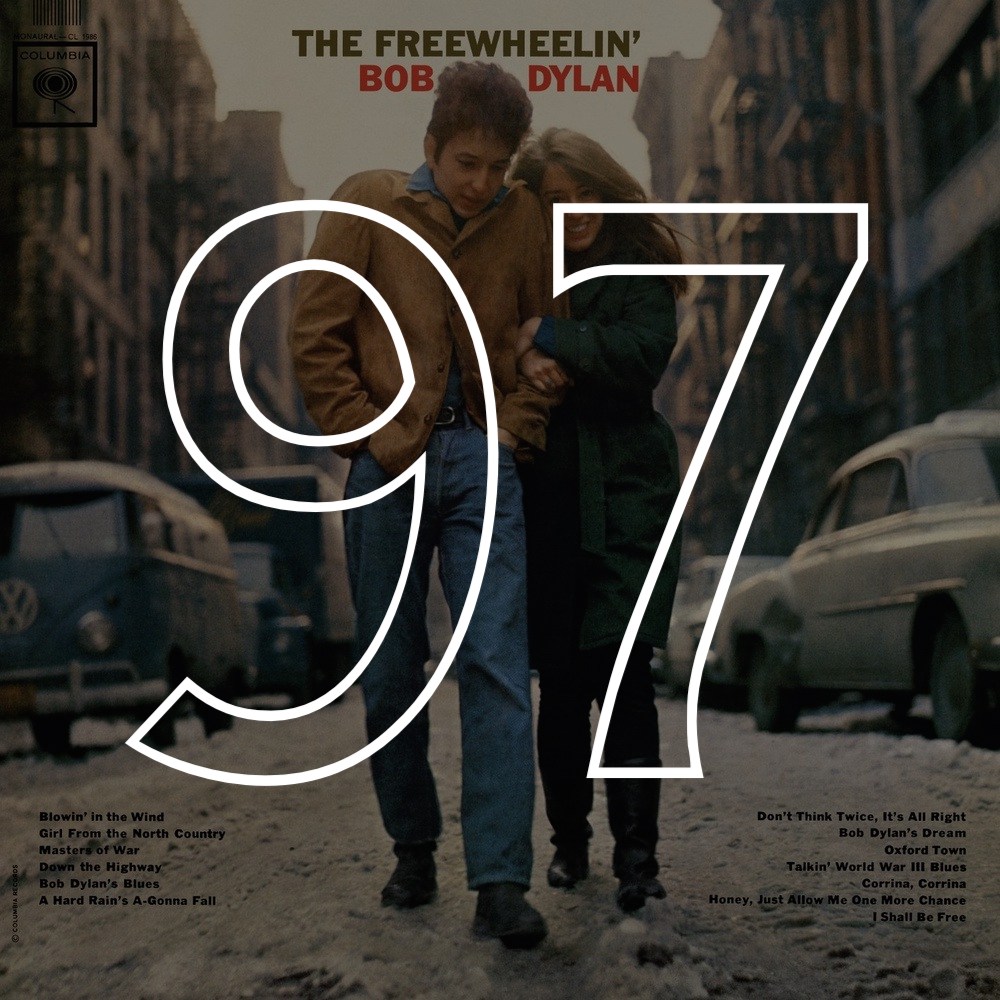

#97: Bob Dylan, "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan" (1963)

I hate the mall. That singular, non-count noun—“the mall”—that stands for every mall in America. The flashy coercive storefronts, the profuse consumer goods, the clumps of shoppers slouching down the left side of the walkway—this is America, ain’t it? At least, the post-war suburbanite version of it. The mall is the American Dream of consumerism writ large, oxygenated and illuminated, protected from the elements. It represents the modern public square of our democracy: mediated by materialism, co-opted by corporations, insulated by artificiality. I get there and I want to leave, but I still get there.

Today I’m going for a pair of boots. I’ve lived in Boston for a few years now, and I still haven’t found the right winter footwear. So I slide on jeans and a sweater, lace up my sneakers still damp from tromping through last night’s snowmelt, and catch the Green Line trolley outside my Brighton apartment. In the back of the train I plug in my headphones. I punch up Bob Dylan’s second album, 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and hear a youthful Dylan sing, “How many roads must a man walk down,” softly, over light strumming, “before you can call him a man?” The song is tranquil, hummable. It bespeaks the gentler side of a northeastern folknik subculture that embraced acoustic, conscientious music as a means of social action.

And “Blowin’ in the Wind” is one of the most famous “protest” songs of the early ‘60s folk revival. Yet the first time Dylan played it live, at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village, he declared, “This here ain’t no protest song or anything like that, ‘cuz I don’t write no protest songs.” Even then, Dylan didn’t just reject labels; he actively refuted them. His only branding is his music.

Oftentimes, the songs come quick. Throughout his career, Dylan has claimed it only took him ten minutes to write “Blowin’ in the Wind.” “It just came,” he told Ed Bradley in 2004. “Right out of that wellspring of creativity.” By the time of that interview, the youngster from the Freewheelin’ cover, strolling through New York in jeans and a thin brown jacket, an inch of snow on the ground, his girlfriend Suze Rotolo on his arm, was a vague remnant in the shadows of Dylan’s face. The laugh lines around his mouth had twisted into a permanent smirk. His eyes were piercing, his face rigid. Hair still dark and curly, he wore a black shirt, gray jacket, long coat, leather pants. In his fingers he nervously twirled a pen. During the interview, Bradley chuckled often; Dylan rarely did.

A decade later, Dylan again commented on writing “Blowin’ in the Wind,” this time while delivering an acceptance speech upon winning the 2015 MusiCares Person of the Year. “If you sang ‘John Henry’ as many times as me…you’d have written ‘How many roads must a man walk down’ too,” Dylan claimed. So the songs come from “that wellspring,” but they also come from history, from habit, from Dylan putting himself in their way.

Dylan acknowledges his predecessors, crediting himself only for sitting with the music long enough for the tunes to channel through him. And yet, the “how many” repetition that initiates each line isn’t found in “John Henry.” The repetition is Dylan’s invention, and it allows him a string of crucial inquiries that weary the reader with their enormity. “The answer,” he finds, is “blowin’ in the wind”: ever-present yet invisible; undeniable yet indefinable; springing not from man’s logic, but nature’s wisdom.

I’ve heard “Blowin’ in the Wind” a hundred times or more, but there on the train, Dylan’s rhetoric envelops me. It almost makes me forget I’m headed to The Mall.

*

The American shopping mall was a staple of suburban life from the mid twentieth century through to the Great Recession. Capitalizing on automobiles and interstates, financially privileged white folks fled the cities, seeking a comfortable homogeneity in a mass of suburban communities. Cars allowed those wealthier white people to adopt long commutes to work, and when it came time for shopping, their wagons and sedans—eventually SUVs—provided ample room for copious bags of purchased goods. In recent years, however, a variety of factors has led to The Mall’s decline. The internet has obviated the need for one-stop shopping; meanwhile, suburban Baby Boomers have seen their privileged offspring flea the suburbs and repopulate urban centers, gentrifying the most economically vulnerable areas.

Though parts of Boston have certainly seen their fair share of gentrification, it’s always been a college town, stuffed with young adults studying, working, frolicking. Out where I live, those students and young professionals fill five-story apartment buildings shouldering every street. From my vantage on the train, the second track of Freewheelin’, “Girl from the North Country,” transforms those blocky blonde-brick apartment buildings rolling past into the seaside Yorkshire hillocks.

Dylan derived the melody for “Girl from the North Country” from the English ballad “Scarborough Fair,” just as he borrowed most of the melodies on this album. He wrote the words, though, to all but two of the thirteen songs, and he told Rolling Stone in 1969, “I felt real good about doing an album with my own material….And I picked a little on it, picked the guitar, and it was a big Gibson—I felt real accomplished on that.” This sophomore effort also includes such songs as the finger-pickin’ “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright”; the condemnatory “Masters of War”; the simultaneously whimsical and haunting “Oxford Town.” Dylan’s own late-adolescent output announced his presence as a formidable new force in American music.

The freewheelin’ Dylan persona contains much emotion and complexity, a pairing that enlivens the student-busy streets of Boston University. As we turn toward downtown, the number of faces in my vision increases like the litany of images now filling my ears from track five, “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.” The diction of the English ballad returns here, tinged with nursery rhyme, a parent asking their child, “Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?” The answer contains “misty mountains,” “crooked highways,” “sad forests,” “dead oceans.” And it concludes with a haunting revelation, rendered in everyman dialect: “It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall.” Images grotesque and foreboding flow forth—“I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken / I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children”—suggesting the harm rendered on society by its warmongering officials.

I scoot over in my bench for a young woman to sit beside me on the filling-up train. She turns up her headphones and whips out her Instagram, her shoulder-length hair straight and auburn like Rotolo’s from the album cover. When the couple met, Rotolo was designing flyers for Gerde’s; her family held communist sympathies, and they enlightened Dylan to progress movements and civic protest.

In fact, Freewheelin’ could’ve been even more political, if Columbia Records would’ve permitted it. The original cut contained the song “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” a joking number that features an obsessive speaker hunting for communists, seeking them “up my chimney hole,” “way down my toilet bowl,” and everywhere else. When the speaker runs out of suspects, he turns his suspicion on himself. Dylan was scheduled to play the song on the Ed Sullivan Show in May, 1963, but the censors asked him to pick a less controversial tune. Rather than compromise, Dylan, whose burgeoning career could’ve benefited from the exposure, simply called off the performance. Columbia Records caught wind, reviewed the track and, fearing libel, refused to release a song that claims members of the John Birch Society “all agree with Hitler’s views / Although he killed six million Jews.” Freewheelin’ had already gone to print, and was recalled. Copies of that first Freewheelin’ are said to be the most expensive and sought after records in existence.

*

There are no music stores in the Copley Place Mall, nor are there any in the adjoining Prudential Central, both of which connect hotels and skyscrapers in a sprawling swath of Boston’s Back Bay. Unlike its suburban counterparts, this complex has thrived from the inner city’s growing wealth. I take a deep breath as I push through the revolving door between a Cheesecake Factory and a P.F. Chang’s, get in line behind a string of folks clogging the escalator, and listen while “Talkin’ World War III Blues” pumps through my ears.

The song’s inciting incident, that “One time ago a crazy dream came to me / I dreamt I was walking through World War III” compels Dylan’s speaker to the doctor, who tells him not to worry because “them ol’ dreams are only in your head.”

I pace through the high-ceilinged, halogen-lit corridors, looking for shoe stores and averting my gaze from salespeople lingering just outside their storefronts shilling clothes and luggage, perfumes and colognes. I feel stuck in my head, too. I’m the only one hearing this music, even as preening couples and young families traipse past. All the other solo shoppers also have their headphones in, listening to who-knows-what—top forty, probably, or some podcast—or maybe Dylan. We’re all so engrossed, yet we’re all so isolated, squished into ourselves by commerce and technology even while surrounded by each other.

In Dylan’s dream, he too finds himself isolated, stricken by the very real specters of red scare and nuclear fallout. Propelled by a major chord progression and repetitive musical phrases disrupted by harmonica bleats, Dylan’s song floats between his dreams and his pitiless real-world environs surroundings. “I was feelin’ kind of lonesome and blue,” Dylan speak-sings after failing to connect with the other few survivors, “So I called up the operator of time / Just to hear a voice of some kind.” This speaker inhabits a lonely continuum, existential and unstable, rife with hunger, paranoia, absurdity.

The doctor butts in to say, “I’ve been having the same old dreams.” In the doctor’s dream, though, Dylan isn’t there. It’s just the doctor, alone. And before long, more than Dylan and the doctor, but “everybody’s havin’ them dreams,” caught in their own desolated worlds, frustrated from a lack of connection.

This can’t be true for us. With our apps and our networks, we’re more connected than ever. And yet, the song, the lights, the oxygen all ensnares me in a spell, alone in the crowd. I plop down on a bench in front of a three-story waterfall, the pool at the bottom adorned with small trees and ferns. I’m searching the faces of these passing mall walkers, of the old man with a cane resting two benches over. “I’ll let you be in my dream if I can be in yours,” Dylan concludes. “I said that.”

Forget the boots. I want to know what that old man’s thinking, what everyone’s dreaming. I want to know if there’s room enough in any one dream for the all of us.

—Paul Haney