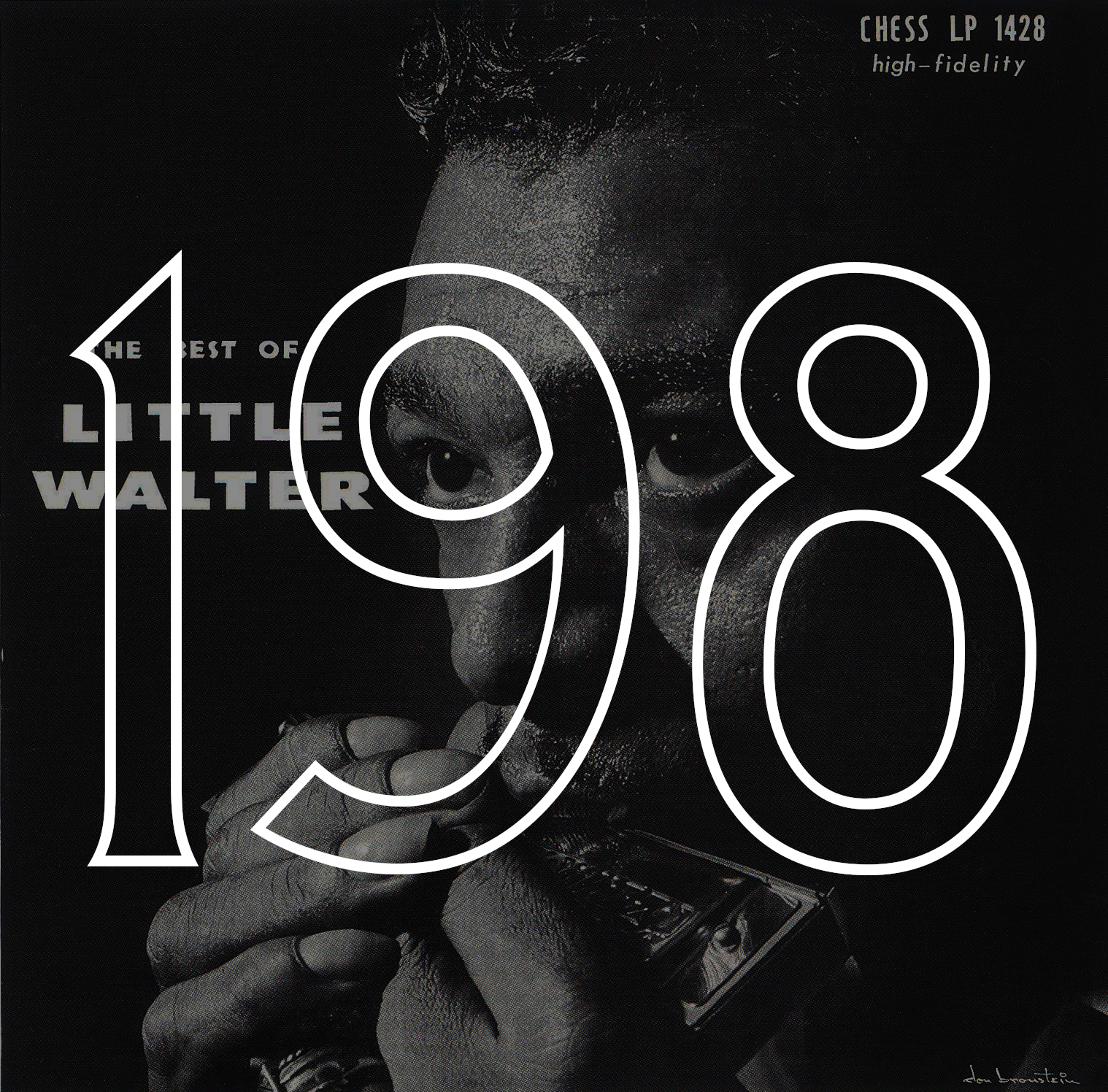

#198: Little Walter, "The Best of Little Walter" (1958)

I was classically trained on the piano, taught to sit up straight with my wrists suspended in the air. Poor posture could cost you points in a recital, or at least that’s what my piano teacher would tell me. She was so set on perfection. To her it didn’t even matter if I was playing the right key if it was with the wrong finger, and she would immediately smack my hands if she caught me doing it. I wouldn’t get very far into Mendelssohn’s Hochzeitsmarsch before you’d hear the cacophony of my mistakes, the sound of my hands pressed forcefully against the keys. She was the devil.

My Senior year of high school, when our jazz ensemble pianist had graduated, I was asked to fill in, since our band director knew I played piano. Fuck, I didn’t know the first thing about jazz. Still, I went along with it because, well, they were so cool...like a bunch of band kids who went rogue. Every class, before we officially started rehearsal, our director opened the floor up for any improv. The drummer picked a beat on his hi-hat and the bass played a chord progression, and then people were given about 16 bars to play whatever they felt. That’s what jazz is all about, the metamorphosis of a feeling into music.

With no notes on a page to tell me what to do, I became acutely aware of my own rigidness. I would freeze, afraid of making a mistake. For hours after school, in the practice rooms where most band kids would go to make out, I would sit there and plan all my “improv” pieces, 16 bars’ worth. It wasn’t until the end of that year that it clicked: if jazz and blues is all about feeling, then it doesn’t need to make sense. In “Sad Hours,” there’s a part where Little Walter leans on the same note, he just wails it out over and over again, he didn’t give a fuck. He was musically unpredictable.

Little Walter reinvented the harp. When I first listened to “Juke,” one of the songs he’s most well known for, I kept waiting to hear a harmonica. Instead, from the sound of it, I pictured something like a trumpet with a mute? I’m not really sure, but definitely not a harmonica. Little Walter didn’t just make music, he brought new sounds to life. He pressed his harp right up to the mic and turned the amp all the way up, setting it free. While he stayed in the band with Muddy Waters for some time, he was too volatile to stay in one place. That kind of genius couldn’t possibly be contained. It would be like trying to pull a comb through Einstein’s hair.

I interject here, because recently, while writing this, there was a protest in Charlottesville, Virginia over the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. White supremacists united under the stated goal, “to take America back.” I watched the news coverage of the rallies, and was confused. The party chanted things like, “You will not replace us.” A part of me wishes I could pull one of them aside and honestly ask, What do you mean “replace you”?

At the turn of the 19th century, racism and prejudice were rampant, but I didn’t have to tell you that. Police brutality didn’t just suddenly become a thing because someone decided to tweet about it. Needless to say, there were A LOT of feelings, and out from the mud of the fields and the streets, the blues were born. But few people give credit to artists like Little Walter, Muddy Waters, or Bo Diddley, let alone even know their names. Ask anyone who Elvis Presley is, and they’ll tell you, “The King.” Some might recognize Willie Dixon’s song, “My Babe,” because Elvis recorded a live cover of it. However, this song was originally recorded by Little Walter and was a number one hit on the Billboard R&B charts. It’s funny how Little Walter’s own wandering and seemingly aimless spirit would become the roots or part of the foundation to legends like the Rolling Stones. He taught people after him how to feel with music, and they inherited the keys to the kingdom without the scars of oppression. So, I ask again: What do you mean “replace you”?

—Yuna Lee