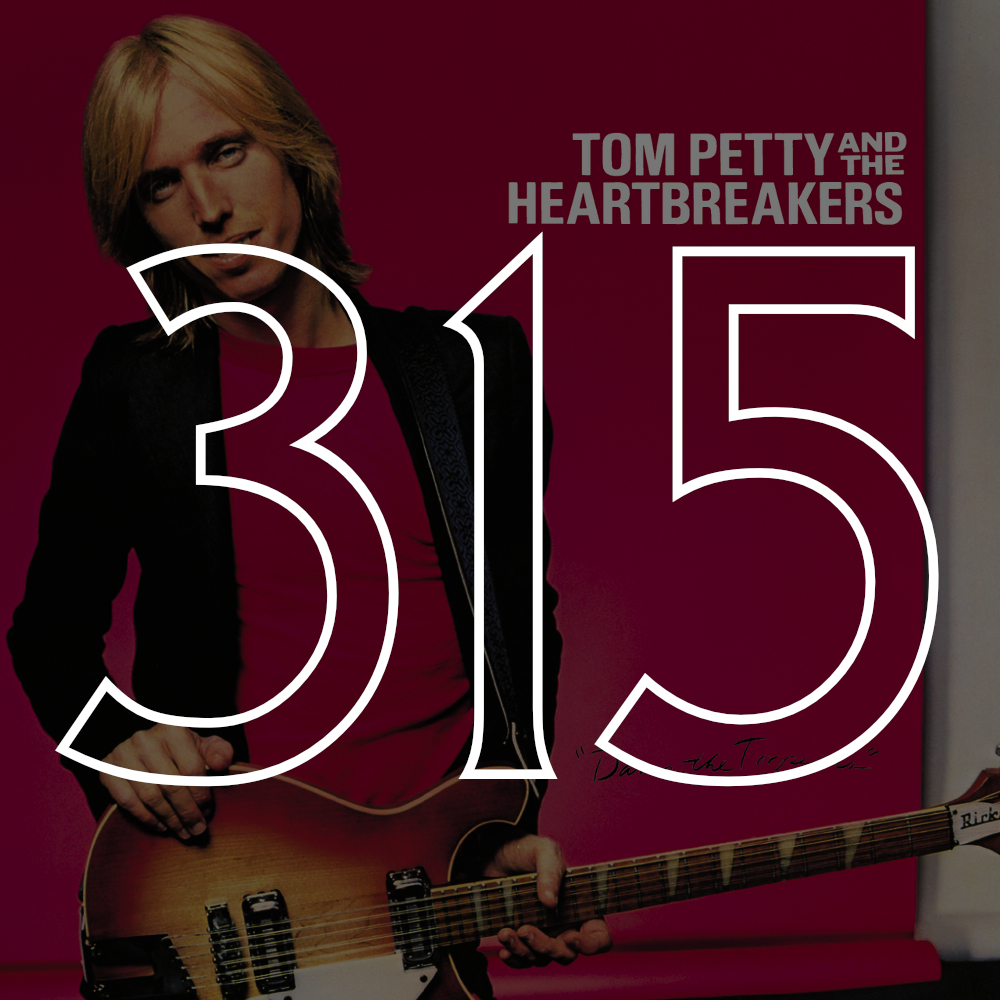

#315: Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, "Damn the Torpedoes" (1979)

I sat down to write this without a glass of wine. This is an essay about music, not food or drink, and I made a rule for myself that I wasn’t going to write about my diet—and so, naturally, I’m opening by mentioning my diet. I can’t help it—it’s my newest challenge, my game with myself, the current self-improvement project at the center of everything. Anything can remind me of it—it exists, nonstop, in my thoughts, on a hum level.

I’ve started the Whole 30—if you’re not familiar, it’s a pretty restrictive elimination diet, designed to last for thirty days. The idea is, you go without a bunch of foods that fairly commonly cause inflammation or digestive issues or general malaise, only eating vegetables, meat, seafood, eggs, fruits, nuts, and healthy fats for long enough for those other foods to work their way out of your system. Then you reintroduce the problem foods, one by one, to get a clear idea of how each one affects you. You can’t know how the foods affect you without first doing the elimination diet, the logic goes, because the effects of what you eat regularly just become part of how you think normal feels. The Whole 30 is designed to show you a new, better normal, so you can be a new, better person.

I am a sucker for attempts to be a new, better person.

And so, now, I am listening to Tom Petty sing on Damn the Torpedoes and he is testing the limits of my willpower. Something in this music really makes me wish for a drink—the jovial, relaxed kind of drink. The drink you pour and take out on your porch with a book in the late afternoon on a mild summer day. Or the beer you crack as you laugh at someone’s joke at a barbecue. (Do you know what else I’d like? A chemical-filled hot dog in a corn-syrup-ey bun—yep, I said corn syrup, because that’s what’s in those things—and a handful of potato chips, and an ice cream cone.) (I am making it sound like I enjoy this diet less than I do, though. Tonight for dinner I am topping a Portobello mushroom with sautéed kale and an olive-oil fried egg, and eating it with a tomato-basil salad, and if I’m being honest all of that sounds pretty excellent to me, which is the real reason I’m undertaking this whole enterprise. It’s something I want to do, something I’m finding I enjoy doing. Right now, at least. In my current mental state. Except for when I’m missing the drink I’d prefer to be having.)

Tom Petty sounds like the rebellion of our fathers. Rebellion in sepia tone. A rebellion of nostalgia, at a far enough remove to have lost the danger and the fear that is part of a rebellious upheaval—a rebellion you’ve already lived through, so you know you make it out in one piece, and in memory it becomes safe.

I think that’s part of what I’m trying to do with this ridiculous diet—grow up and banish all irresponsibility to the past. Insulate myself from it, transform it into something more muted and containable. Not even permanently, really, but I feel a deep-seeded need to, at least for awhile, prove to myself that I can act like I always envisioned adults would act.

For awhile I thought I would have children, and I figured that the hazy future when the children came would be the thing that would make me grow up, the thing that would catapult me into adulthood and force me to make better decisions. But I find myself wanting to make better decisions without that inciting event (or maybe with a series of different and subtler inciting events—the gradual creeping change in what we desire). I feel more capable of having my shit together than I ever have, which makes me want to do it. And my life is in flux in many ways—I owe it to myself, I think, to seek stability and self-care when any opportunity for those things presents itself. And, also, to make it one of the projects of my life to create those opportunities whenever I can.

As I decide not to eat toast or coconut shortbread cookies or sharp cheddar cheese, as I decide not to drink chardonnay or a screwdriver or even Diet Coke, as I cook each meal for myself every day from a selection of food delivered to me by my local CSA—as the cutting board takes up near-permanent residence on my counter—I say to myself, you are doing the hard work of creating new habits and standards, habits and standards that will serve you well as you deliver yourself into adulthood.

Damn the Torpedoes was Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ third album, and their first to go platinum. It came out in 1979, when Tom Petty was 29. This is the same age I am today. Something in the symmetry of this pleases me, even though the feeling his music embodies for me is something I no longer feel like I live inside. Not living inside it allows me to love it more.

Tom Petty sings like English is another language. But it isn’t—just our own made foreign with an emphasis on the guttural and murmured. It is visceral and dramatic, the way that youth is. It tastes of risk, of heartbreak—not just the kind that happens when we open ourselves to others. The ways we break ourselves. Don’t do me like that.

There were years when, after several drinks, I’d head out to the porch and bum a cigarette and inhale. For a time I liked it. I didn’t want to become addicted, and took care not to do it often, but I cherished the lightheadedness and the ease and the excuse to talk to a man. It gave me something to do with my hands. I felt worldly, and like I had purpose, in a way that you can only feel when you are playing at a thing rather than being it. When I think of that past self, I feel such tremendous affection, in a way that I only can because I feel so very far from her now. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers live with her and her cigarettes and the cheap frat house whiskey and the bars we shut down whose floors were sticky with beer. They stay up all night for no reason, these past selves, and eat pizza and french fries for dinner, they eat nachos at 3 a.m., and they sleep with all the wrong people—they feel very lost and scared but it’s all part of the excitement. There is plenty of time for them to figure out what serious things they want to do sometime later. And we love them dearly for it. They remind us that we have muddled through.

—Katelyn Kiley