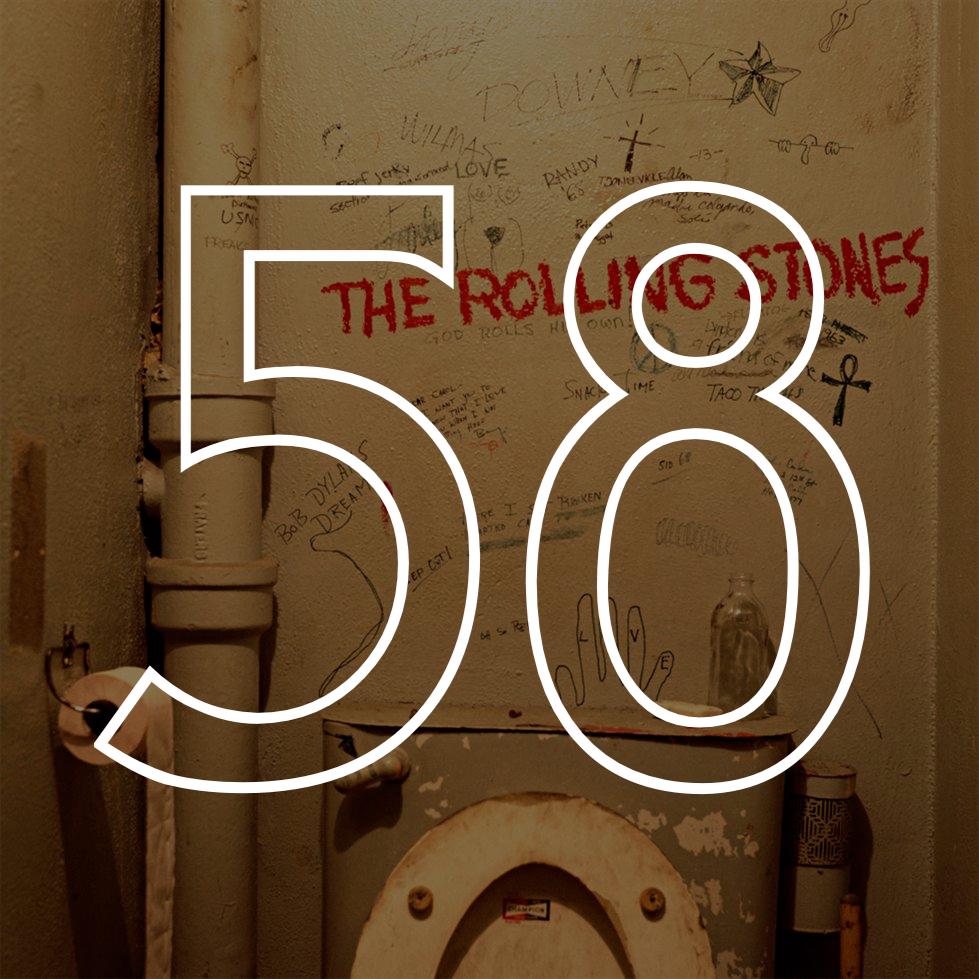

#58: The Rolling Stones, "Beggars Banquet" (1968)

There he is. You can see him only from behind, in slight profile at times, but the blonde bobbed hair gives it away. Brian Jones, sitting in a tight circle alongside Keith Richards and Mick Jagger as the Rolling Stones rehearse “Sympathy for the Devil” in the recording studio, captured forever in Jean-Luc Godard’s One Plus One. He wears a simple white shirt and a pair of black trousers with fat red and white pinstripes, its matching coat draped casually on the back of his chair. Though you can’t see his face, not really, Jones seems lucid, engaged, tapping his foot in time and throwing blues embellishments into the song’s basic melody.

Later, in another scene, he’s there in a larger circle, recording the “whoo-whoo” backing vocals for “Sympathy,” along with the rest of the band and Marianne Faithfull and Anita Pallenberg. He wears a cream shirt, green bell-bottoms, and has a silk scarf tied around his neck. He reaches up, once, and puts his hand tentatively on Pallenberg’s back before withdrawing it after four short seconds. All this is proof. Proof that he did contribute at least in part to this one song, the first track on Beggars Banquet.

The record’s producer, Jimmy Miller, would tell Rolling Stone that Jones “was sort of in and out.…He’d show up occasionally when he was in the mood to play, and he could never really be relied on.” By this point, Jones’s erratic behavior was fairly common knowledge, a side effect of his psychological struggles and drug abuse. The band would patronize him, or to use Miller’s own language, “accommodate him,” when Jones was lucid enough to show up. “I would isolate him,” Miller said, “put him in a booth and not record him onto any track that we really needed.”

But there he is in Godard’s film, playing the guitar, recording backing vocals, both of which Jones would be credited for in the liner notes to “Sympathy.” He would also be credited with acoustic guitar and harmonica on “Parachute Woman” and slide guitar on “No Expectations” and “Jigsaw Puzzle,” but most of his contributions to Beggars Banquet would be ancillary: Mellotron on “Stray Cat Blues,” sitar and tambura on “Street Fighting Man,” harmonica on a few songs. He’s given no credit for the album’s final tracks, “Factory Girl” and “Salt of the Earth.” Quite a fall for the man who had founded the Rolling Stones a mere six years prior, the man who gave them their name and their earliest identity, who had created their trademark “guitar weaving” sound with Richards.

At the end of the year, the band would film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. There’s Jones, one of the most talented multi-instrumentalists of his day, a prodigy seemingly adept at playing any instrument put in his hands, reduced to shaking the maracas on “Sympathy for the Devil.” On “Jumping Jack Flash” and “Parachute Woman,” Jones wears his guitar more than plays it, the instrument looking every bit as ill-fitting and affected as his oversized purple coat and baggy yellow pants. And at the end of the show, during the mass sing-along to “Salt of the Earth,” he’s there, between Richards and Charlie Watts, swaying out of sync with the rest of the crowd, unable to remember the words to the song. This would be his last formal appearance with the band.

Seven months later he would be dead, found at the bottom of a swimming pool. “Death by misadventure” as the coroner’s report so poetically put it.

*

Contrast these images with the Brian Jones in this video of the Stones playing “Paint It, Black” just two years earlier in 1965. Here he is, sitting cross-legged on the stage, dressed all in white, smiling, looking directly into the camera, his entire body moving in time with the song as he plays the sitar. This Rolling Stones is still his band, his and Jagger’s, Keith Richards merely a backing figure who the camera never focuses on.

Read the comments on the video and you’ll see that for many fans, the Rolling Stones never stopped being Jones’s band, even almost fifty years after his death. “Brian is still the Original Stone!” one user says. “Brian was the inspiration and most talented member of the group,” another comments, “I miss him.” Another poses the question, “Why does it say ‘with Brian Jones’ u mean Brian Jones ‘with The Rolling Stones.’”

So many fans still hold up Brian Jones as this romantic ideal, Adonis, the original member of the “27 Club” of icons dead before their time. He was the tortured genius, the beautiful martyr, the hard partying rock god. Such idolatry is easy; it has created this romanticized myth of Brian Jones, a myth far sexier than the reality.

It’s this myth that leads fans to comment on a YouTube video, “All their ground breaking songs…were written when Brain Jones was alive. After Brian died and Mick Taylor joined the band, they were no better than a generic garage band.”

*

But like all myth, the myth of Brian Jones is a good story that reveals more about the teller than it does the subject. Because Brian Jones was not the Rolling Stones. He formed the band, gave them their name, gave them their sound, but what they achieved had far more to do with other contributors.

Their achievements had more to do with Andrew Loog Oldham, the manager who encouraged the Stones to write their own songs, to move away from the blues covers that Jones insisted on. It had more to do with Jagger and Richards, both their songwriting power and their pure embodiment of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. It had more to do with the band’s ability to sell itself, both its sound and image, while creating complicated business ventures that allowed them to circumvent British tax laws and become one of the biggest rock bands to ever exist.

None of this would have happened without Brian Jones, but most of it happened without Brian Jones.

In fact, the Rolling Stones’ generally agreed upon “Golden Age” of 1968-72, the years they released what many consider their greatest albums, were years in which Jones played little to no part. Beggars Banquet is the start of this Golden Age, and Jones’s contributions were hardly integral. Jones would supply congas to “Midnight Rambler” and autoharp on “You Got the Silver,” but otherwise he played no part in Let It Bleed. He would be kicked out of the band shortly after, and shortly after that he would die in the swimming pool of his farmhouse in East Sussex. Both Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street would be written, recorded, and released after his death. These four albums are largely the Rolling Stones’ greatest contributions to music, and Brian Jones had nothing—or almost nothing—to do with them.

*

Myths reveal more about the teller than they do the subject. So what do these myths tell us about Brian Jones? We have the myth told to us by those who were there—Jimmy Miller, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, countless others—of Brian Jones being completely absent by the time the Golden Age began in 1968 with Beggars Banquet. We have the myth of the idolizing fans of this Adonis, blonde, beautiful, smooth and sleek in a way that Jagger and Richards never quite were, the only true genius of a group who were reduced to “a generic garage band” after he left.

Yet we have these films shot in 1968, One Plus One and Rock and Roll Circus, that show neither myth to be true. Because there he is in Godard’s film, contributing to the recording of Beggars Banquet, giving at least something to the Rolling Stones’ greatest era even if his influence on the band was all but over. For his bandmates and producer, his frequent absences and erratic behavior, his utter surrender to his addictions, likely caused enough frustration that they wished he weren’t there, but there he was.

But the Brian Jones we see in Rock and Roll Circus is no god. He is a puppet, propped up and stumbling through the motions, shoved off to the side where he can be hidden as the camera zooms in on Mick or Keith. He strums his guitar and raises his hand like he remembers raising his hand to strum dramatically, to be the rock god he remembers himself to be, but his hand is limp and the movement without conviction. This Brian Jones is a tragic figure, certainly, but no Byronic hero. This Brian Jones is pitiful.

*

Go back even further. Go back to that video of “Paint It, Black” from 1965. Notice that, even then, Jones is removed from the band. He is on a separate riser on the left of your screen so that when the camera focuses on Jagger, the rest of the band is in the shot, but Brian Jones is off screen. He is physically above them and removed from them. Despite the YouTube commenters focusing on Jones almost solely, he is on screen for a mere 47 seconds out of the video’s 2:19 runtime. And yet he’s the only member of the band other than Jagger who gets a full close-up.

*

It is nearly impossible to tell the story of the Rolling Stones without Brian Jones. None of what they became would be possible without Brian Jones, but their greatest output was created without Brian Jones.

Prior to 1968, the Rolling Stones produced some fantastic songs and a few decent records, but nothing compared to Beggars Banquet, their first truly cohesive album that functioned as a singular musical statement. Beggars Banquet is their Rubber Soul, the beginning of the Rolling Stones as a band capable of recording an entire LP of brilliance. This was made possible, in part, by breaking with the tired psychedelia of 1960s and by returning to their roots in R&B and Americana.

But part of what made this possible was the loss of Brian Jones the man, even if they could never shake the myth.

—Joshua Cross